A Brilliant History

If a rose by any other name will smell as sweet, what about a diamond? What’s in the name? There have been many stages in the history of diamond cutting practices - techniques and new technologies have been developed to enhance the hardest material on Earth to dazzling proportions. Understanding what is in the name and characteristics behind the look will help to identify the time period in which a diamond was cut which can often help to date a piece of antique jewelry.

As technology has advanced over time, diamond cutting styles evolved to optimize the brilliance of the stone. Brilliance is a term used to qualify the brightness of a gemstone, relating to the amount of internal light reflection. Well-placed facets will increase the amount of light playing and reflecting back to the viewer, and determine a stone’s brilliance. A stone which is cut too shallow or too deep will either allow the light to leak out or absorb all the light, preventing reflection and reducing the brilliance of the stone. Ideal cutting will maximize the amount of light which is reflected for optimal sparkle from the stone.

____________________

Pre-Brilliant Styles

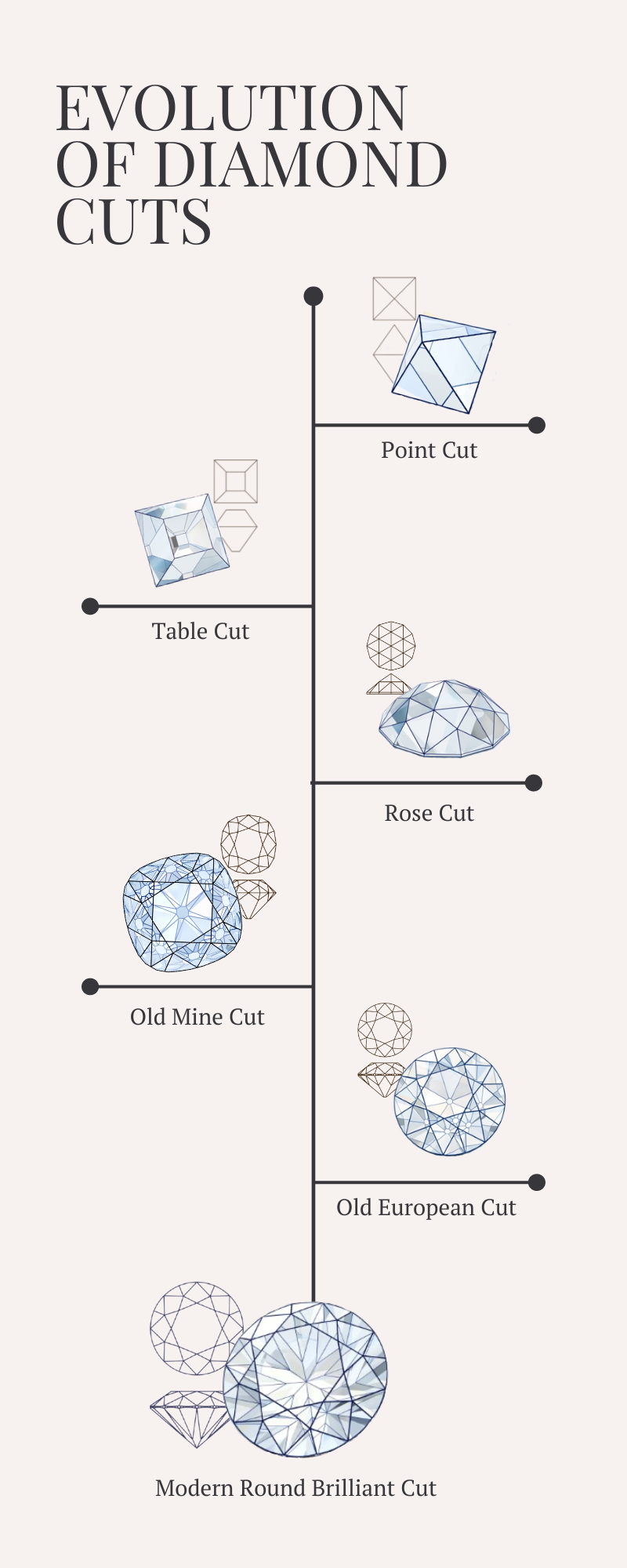

Diamonds are the hardest material on Earth and were prized in ancient times for their strength above all. The practice of diamond cutting began in the Indian subcontinent in the 6th century and European cutting practices starting in the 14th century where the crystal’s original facets were simply polished to even out nature’s octahedral design, called a point cut. The table cut was the next evolution in diamond cutting where one of the points would be ground off, creating the table facet.

The crystal structure of a diamond has perfect cleavage, meaning that when force is applied in the appropriate direction the outcome is an extremely smooth fracture. The byproduct of knocked-off crystals produced these flat, naturally faceted, thin pieces of rough material. By the 17th century, diamond cutters were faceting these thin pieces of precious material, becoming the earliest form of the rose cut. With a flat base and domed shape, the rose cut has no pavilion and features triangular facets covering the crown which meet in a point at its center.

Brilliance like this in diamonds had never been experienced before, and, aligning with advancements in candle making during the Georgian era, rose cut diamonds glimmered into popularity among noble classes of Europe. Helped along by an influx of diamonds into the market from new mine discoveries in Brazil in the early 18th century, demand for sparkling diamond jewelry had never been greater.

____________________

Old Mine Cut - mid 18th century to 19th century (Georgian and Victorian periods)

Having more material to facet produced greater brilliance from a diamond and as the domes on rose cuts were growing larger to accommodate additional facets to catch the light, a new diamond cut was emerging. Overlapping in the Georgian era with rose cuts, this new brilliant cutting style - Old Mine Cut - was being introduced.

Reflecting back on earlier diamond cuts, the old mine cut had a similar shape to the table cut - with its deep pavilion and high crown angles - and was multifaceted like the rose cut. The broad facet pattern in the Old Mine Cut has the wonderful characteristic of producing bold wide flashes in the flickering candle light of the time period. Since the weight of the diamond (the carat part of the 4Cs) contributes the most to its cost, well-made rose cut diamonds continued to be popular through the Georgian Era. Their thin dimensions are more affordable for the same diameter compared to the deeper proportions of old mine cut diamonds.

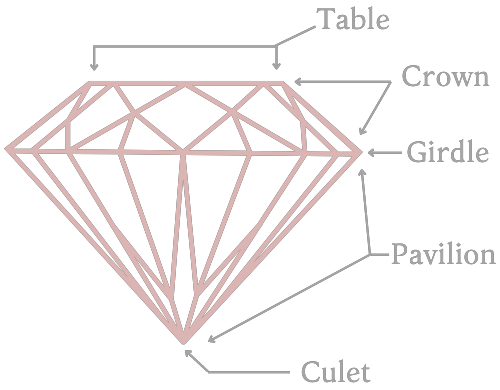

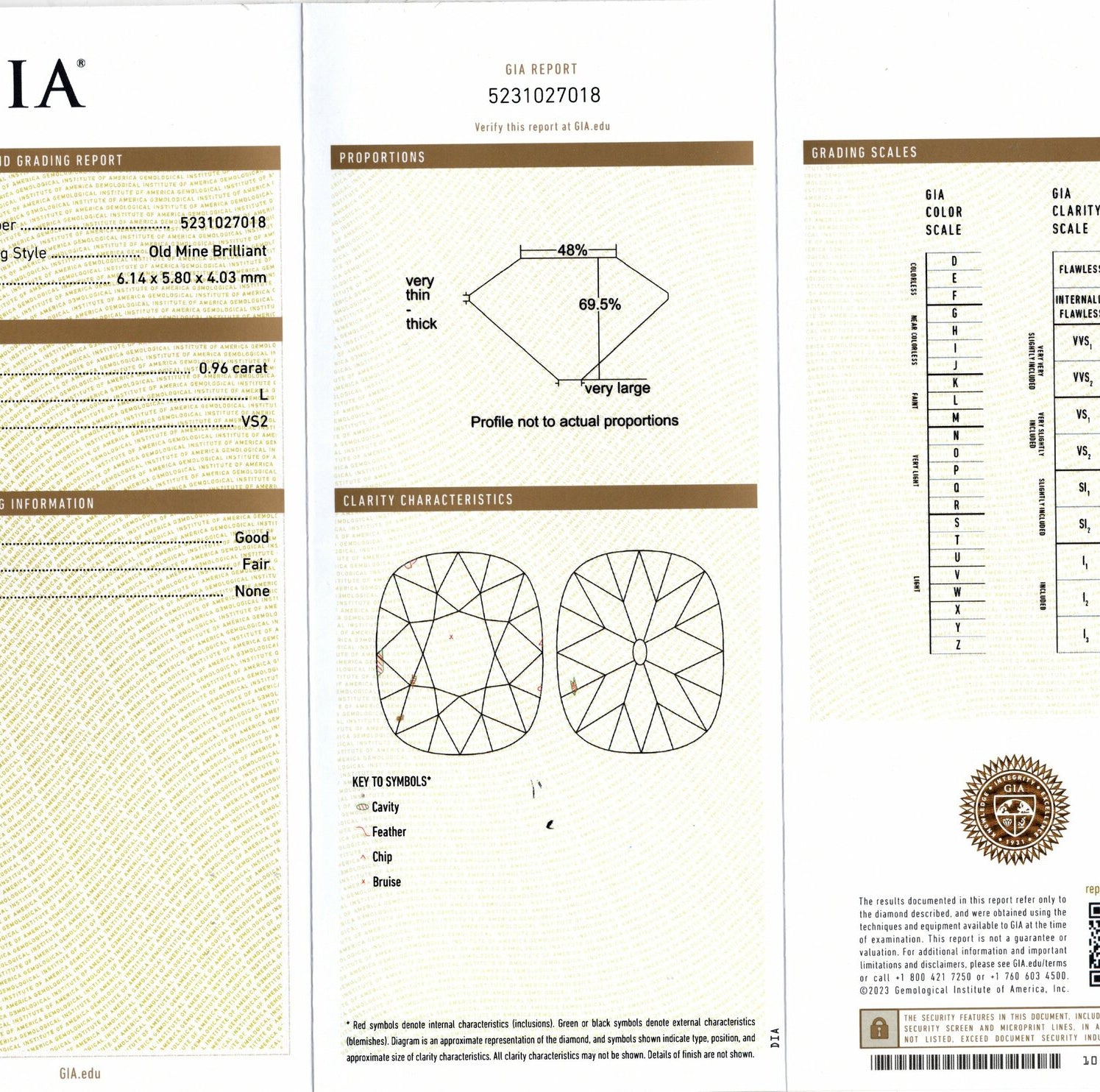

Based on the natural octahedral shape of the diamond in its uncut state, to retain the most weight in the stone there is a high crown angle, deep pavilion, large culet and a small table in an Old Mine Cut diamond.

Since there is not always a consistent and symmetrical shape in the natural stone, diamonds of this era tend to be off-round without a symmetrical outline, often in rounded square and rectangular shapes. Old mine cuts were the most popular diamond shape in the 19th century and its timeless design is reflected in the demand for Cushion Brilliant cuts today.

____________________

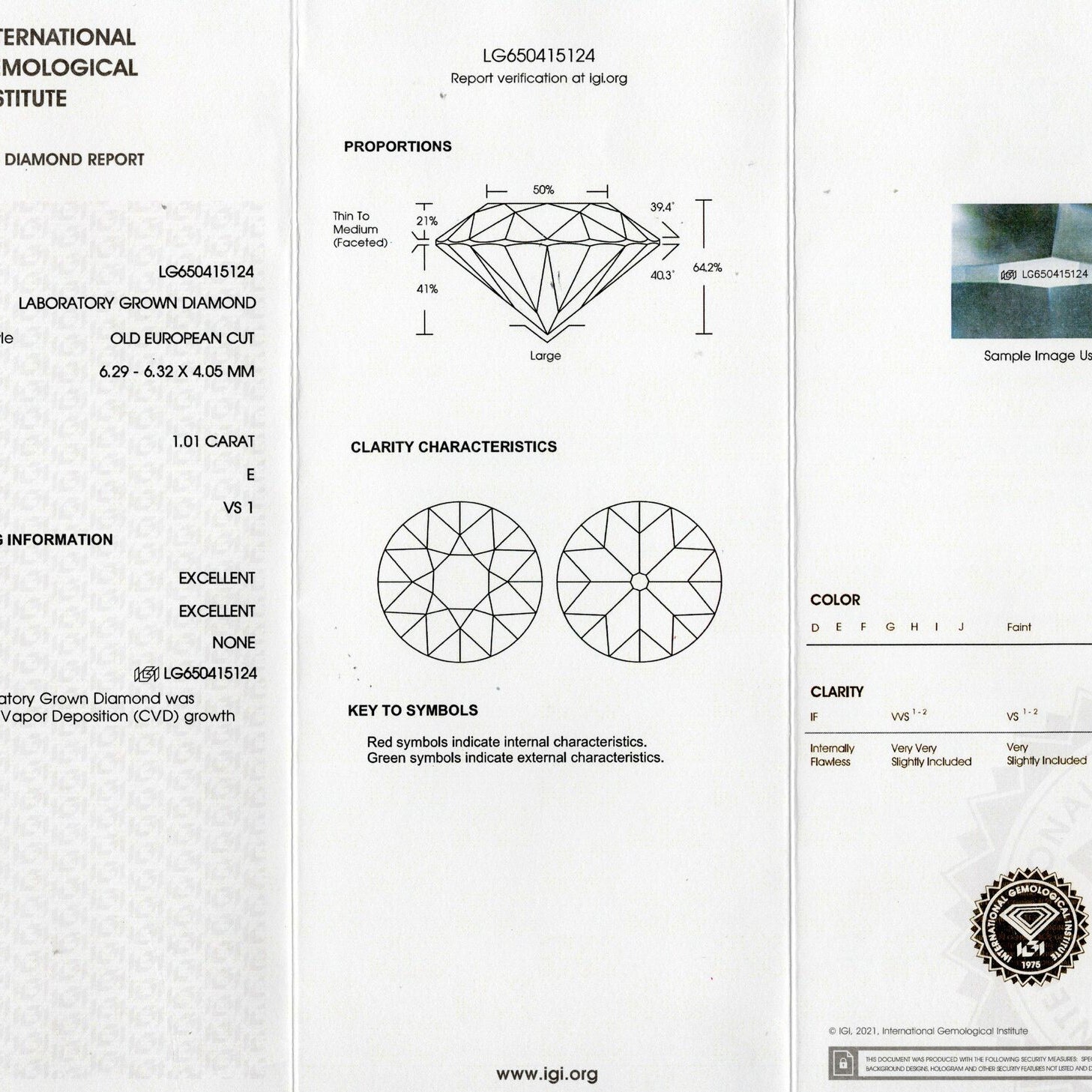

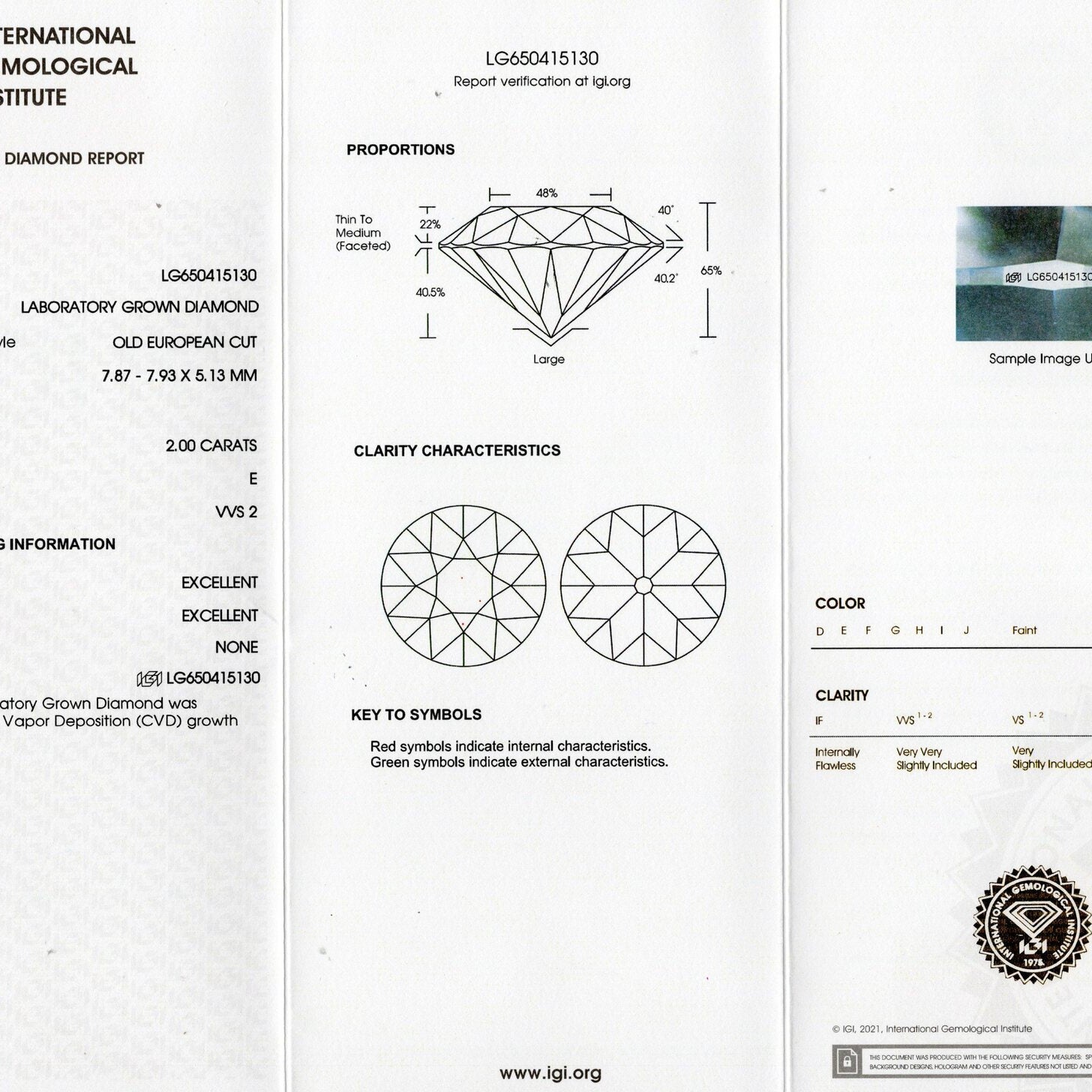

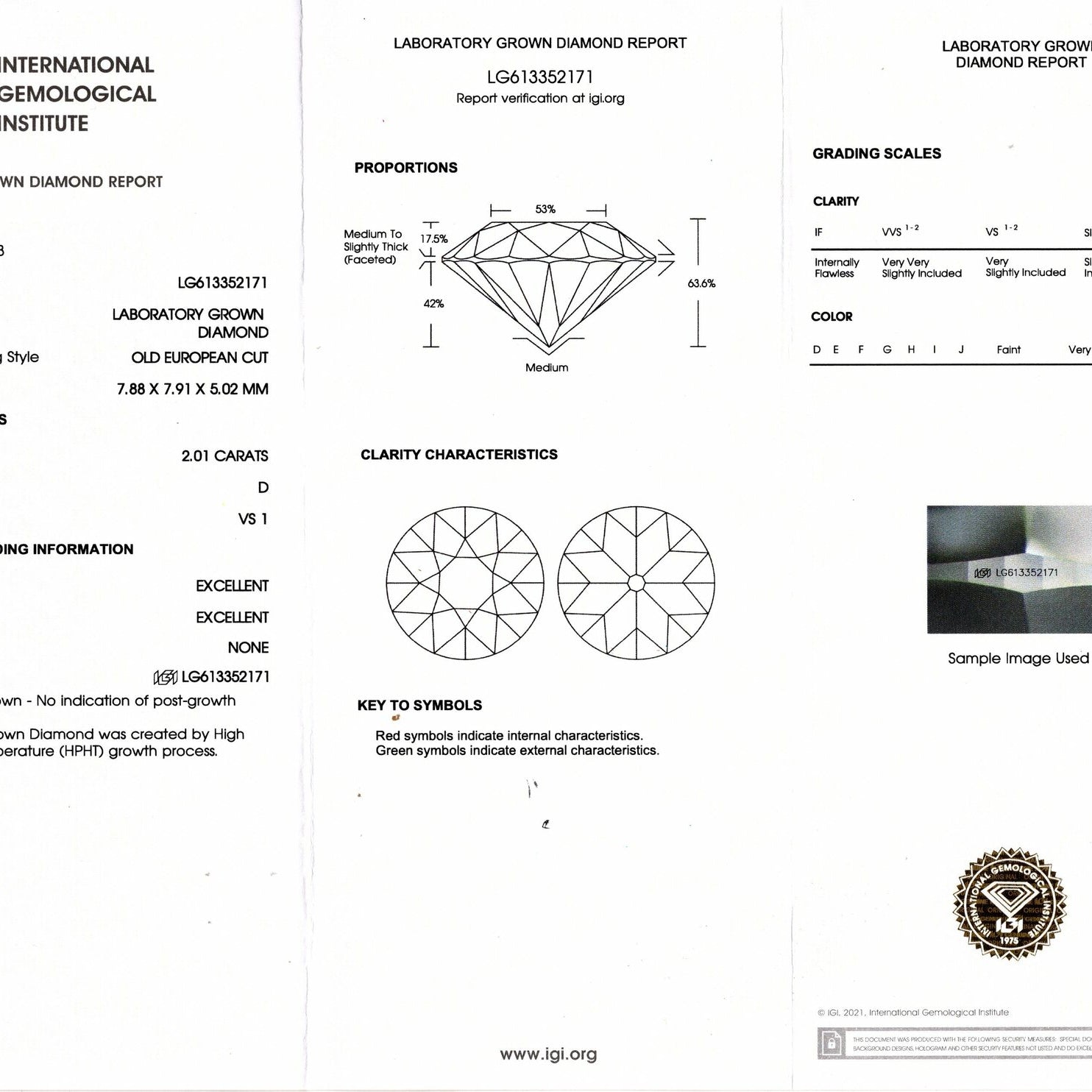

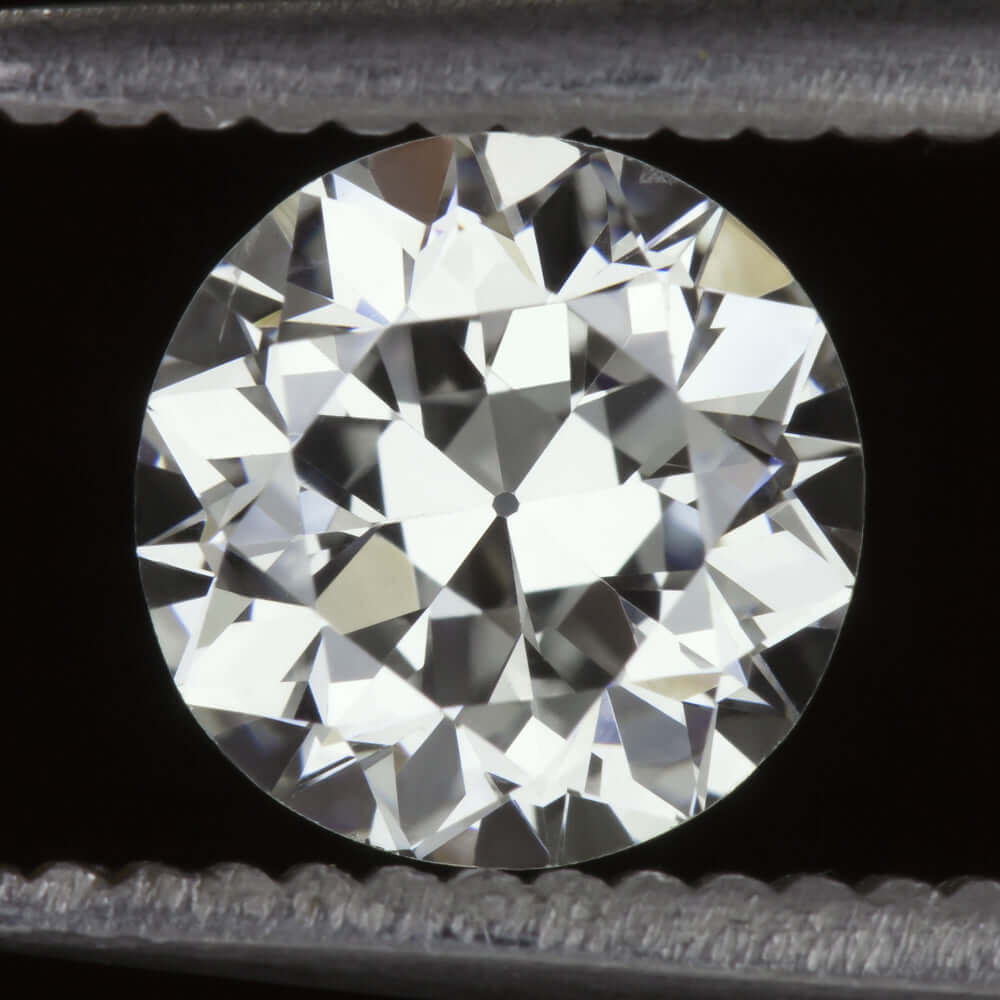

Old European Cut - late 19th century to early 20th century

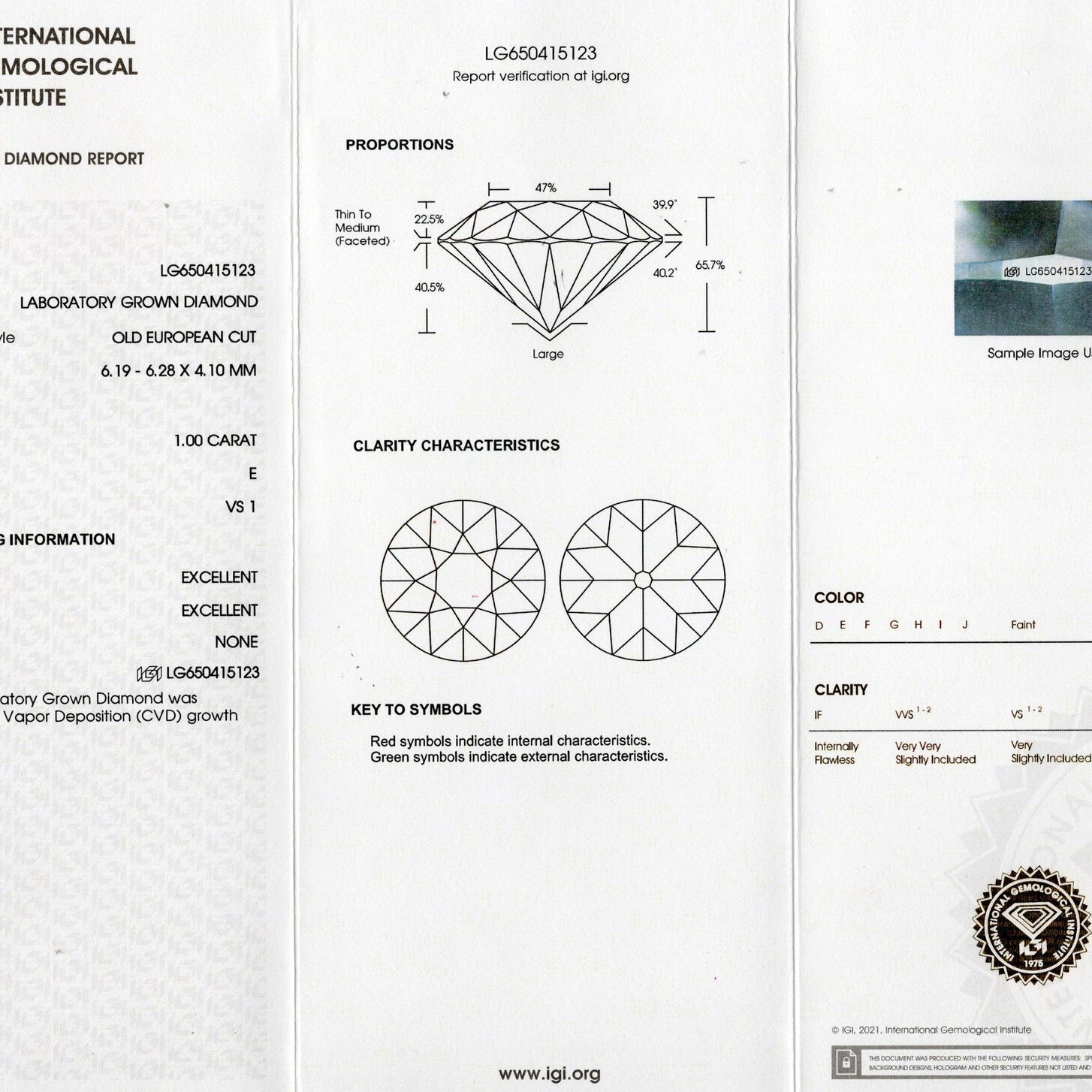

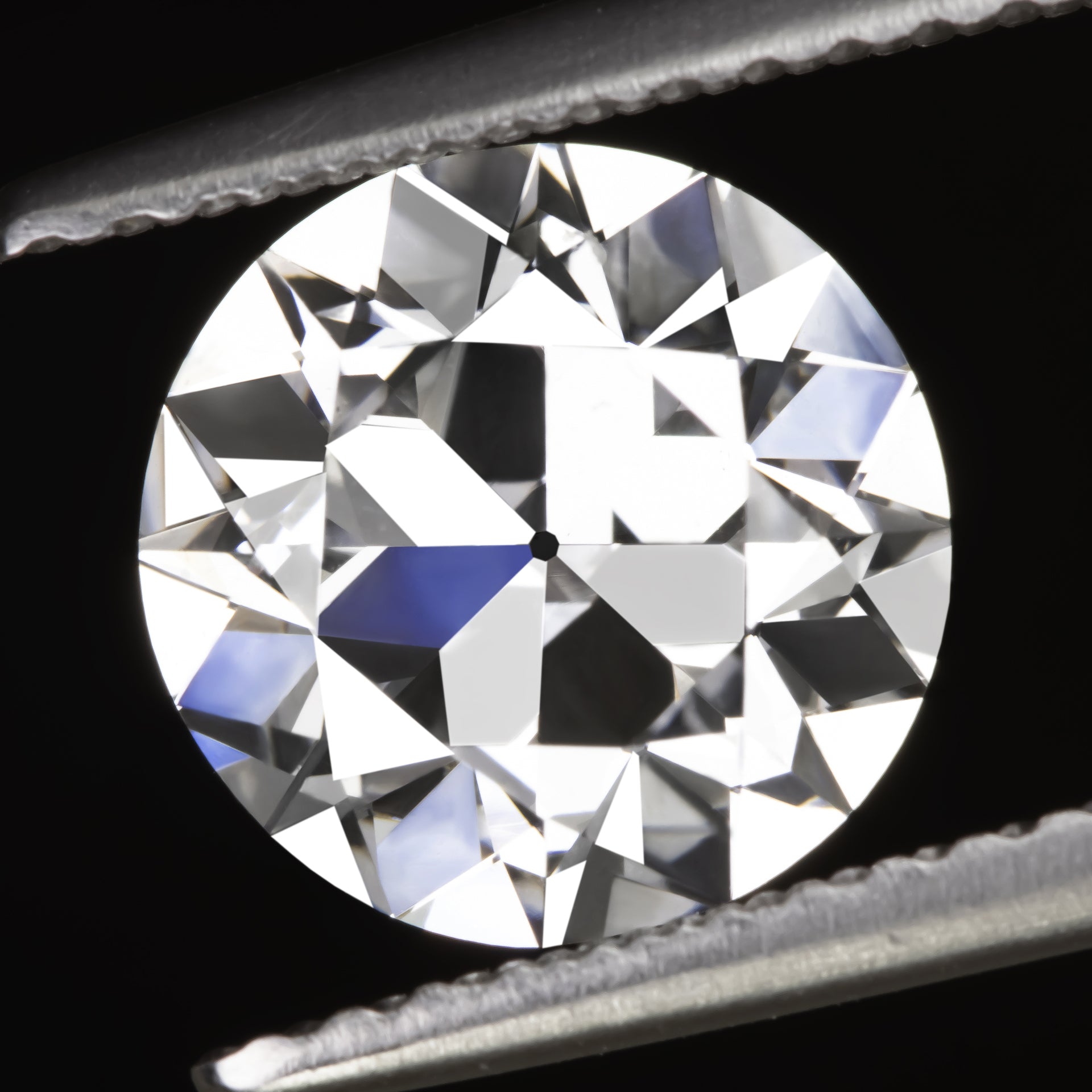

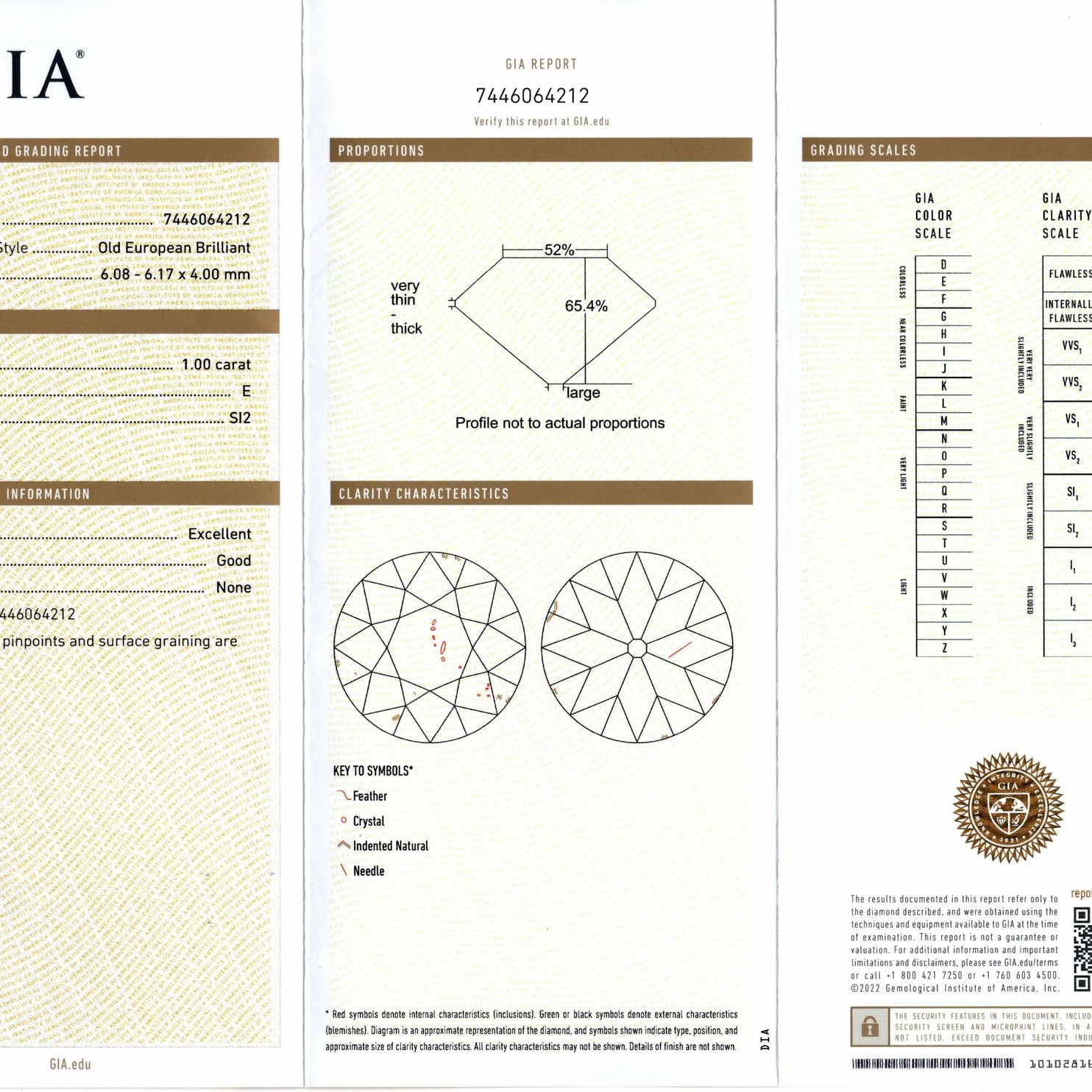

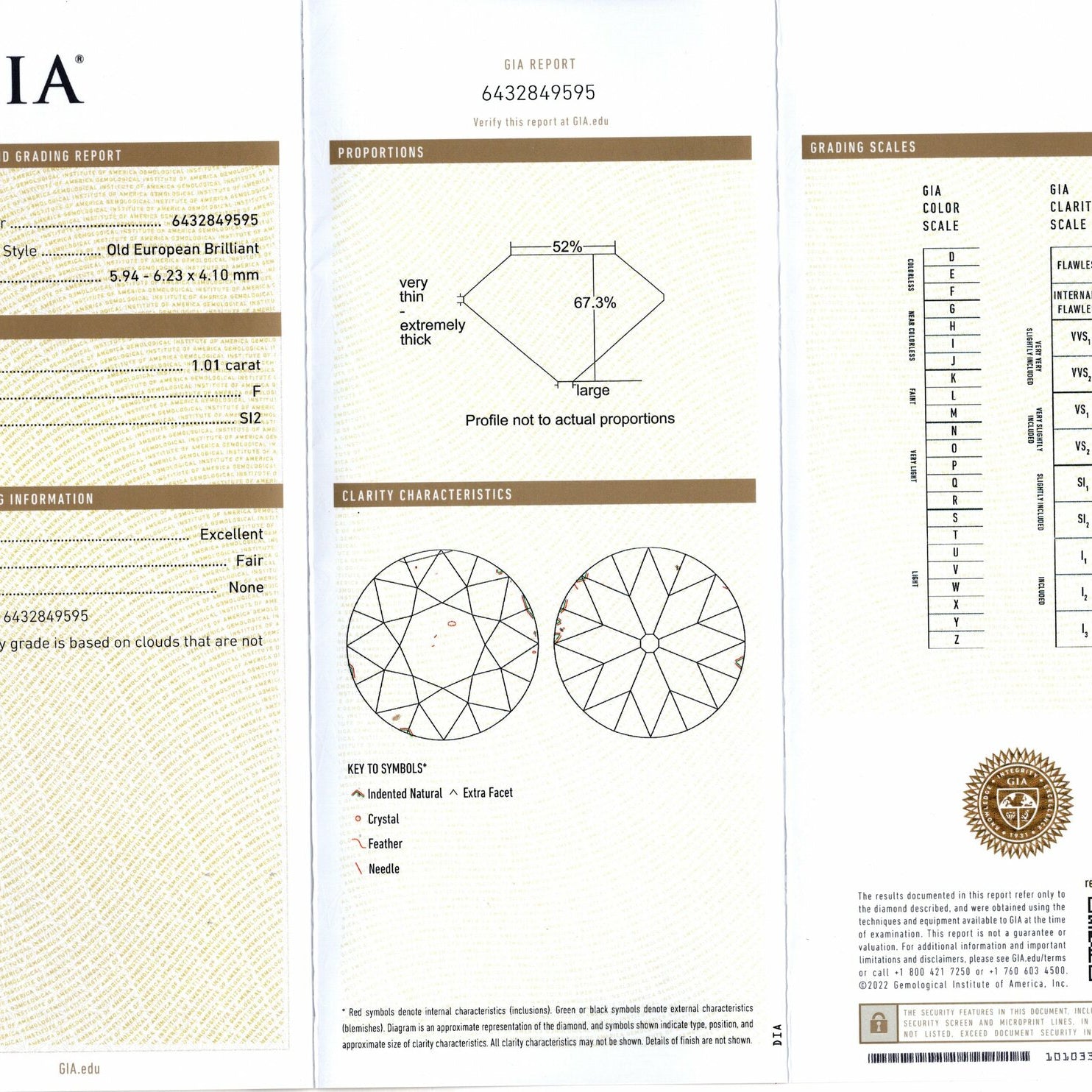

The process of establishing the girdle outline is called bruting and up until this point in diamond cutting history this had been a practice completed by hand. This helps to understand why the outlines of diamonds had been asymmetrical up until this point, as it echoed the shape of the initial rough material. Mechanical bruting was introduced to diamond cutting in the 1870s which enabled more symmetrical outlines and more consistent facet patterns, contributing to this new look which is now called Old European Cut.

The round shape allowed for a more proportional stone with less variability than the Old Mine Cut and symmetry was now attainable in the cutting practice without significant weight loss. With this development, round became the new de facto diamond shape and symmetry became an important factor in the desirability of a stone. Key characteristics of the Old European Cut style include this new round outline, a small table, shallower pavilion than the Old Mine Cut and a smaller open culet.

Old European cuts had their reign of popularity from the late 19th century to early 20th century. There were commercial mines producing more rough during the time when Old Europeans were popular so there are more of them in existence. One mine in particular was a tremendous supplier of diamonds to Europe. From 1871-1914, the Kimberley Mine in the Cape Province of South Africa produced 13.6 million carats of diamonds in the period. Since so much rough material was being mined from a single location, a characteristic of this regional mineral has become another distinctive feature of the Old European Cut and Old Mine Cut diamonds from this era.

Referred to as Cape diamonds, the vast majority of these stones exhibit warmer tones of yellow to brown and would be considered as lower color grades by today’s gemological grading standards. While colorless (DEF grades) and near-colorless (GHI grades) diamonds came out of this mine as well during this period, they are even more exceptionally rare today since these stones were quite often recut to the proportions of modern Round Brilliant Cuts as diamond cutting technology and buyer’s tastes evolved.

____________________

Transitional Cut or Circular Brilliant - early 20th century

Even though the theory for the modern round brilliant cut (RBC) was in place since the end of the 19th century, these theories were not put into practice for 30-40 years later during the Art Deco era. However, this dramatic change did not happen overnight as the world slowly transitioned to this new round brilliant form. Transitional Cut diamonds are not a specific set of proportions or consistent look from stone to stone, but notable shifts are occurring in diamond cutting abilities at this time period where we see a transition from Old European Cuts to modern Round Brilliant Cuts.

The table is getting larger and crown heights are becoming smaller. Outlines continue to become more consistently round. Pavillion depths are decreasing and faceting is changing towards longer, thinner facets. Culets are getting smaller and disappearing to a pointed culet. Since there is not a set of consistent parameters to determine a Transitional Cut style, a diamond cut in this method and time period will be identified as Circular Brilliant if it has been certified by a GIA laboratory.

These rare stones were cut from the 1920s to 1940s and represent a very unique time in history. Today, they are becoming increasingly rare as many are being recut to fully modern round brilliant cuts.

____________________

Round Brilliant Cut ~ mid 20th century-today

Centuries in experimentation and advancements in cutting techniques and technologies from across the globe finally culminated in the modern Round Brilliant Cut diamond. The work of Henry Morse, Marcel Tolkowsky and generations of diamond cutters before them have contributed to the characteristics of the modern Round Brilliant Cut, and it remains the dominant cutting style to this day.

The modern Round Brilliant Cut features a larger table with smaller crown angles. The pavilion is not as heavy as it was in prior centuries and has long thin facets from the girdle down to the pointed cutlet - for the first time, the culet is no longer open. It is these long pavilion facets that create the splintered brilliance which is a key element in identifying a Round Brilliant Cut diamond. The thinner facets reflect even more upon each other, achieving a truly dazzling amount of sparkle.

Since the 1970s, computers have been used to design diamond cuts, and the actual cutting work is now largely carried out by lasers instead of human hands. Precision in contemporary diamond cutting has led to the ability to achieve consistent proportions for a uniform cut and style. Based on the expectation of conformity to these parameters, a cut grade is given only to the Round Brilliant Cut diamond by gemological laboratories, such as GIA and EGL. A Round Brilliant Cut diamond that has excellent polish, excellent symmetry and an excellent cut grade will also be called a Triple Excellent, Triple X or 3EX diamond.

Recent posts

Why Diamonds Are a Smart Investment

While traditional investment options like stocks, bonds, and real estate fluctuate with market trends, diamonds hold a distinct position as a tangible, portable, and enduring store of wealth.

The Smart Investment: Rising Gold Prices vs. Platinum Value

Gold has long been a symbol of luxury, but its soaring prices have changed the jewelry market landscape. With gold costs on the rise, the price difference between gold and platinum is shrinking. This shift means that for only a slightly higher investment you can enjoy the many advantages that platinum offers over gold.

Zendaya’s Engagement Ring: A Modern Twist on the Button Back Setting

Zendaya’s engagement ring, unveiled at the 2025 Golden Globes, has quickly become the talk of the town, blending timeless vintage charm with a contemporary twist. Designed by London-based jeweler Jessica McCormack, the ring features a stunning 5.02-carat cushion-cut diamond set in a unique east-west orientation. But what truly sets this piece apart is its vintage-inspired "button back" setting, which has roots dating back to the Georgian era.